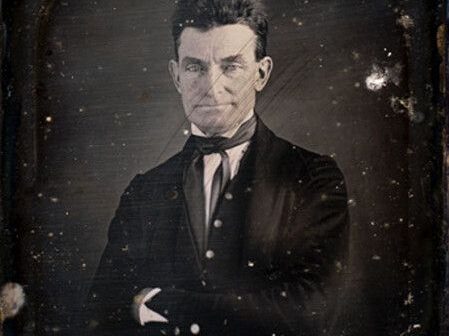

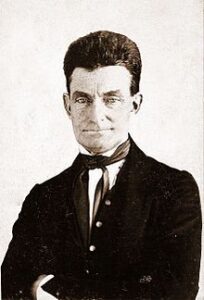

A native of Connecticut, John Brown struggled to support his large family and moved restlessly from state to state throughout his life, becoming a passionate opponent of slavery along the way. After assisting in the Underground Railroad out of Missouri and engaging in the bloody struggle between pro– and anti–slavery forces in Kansas in the 1850s, Brown grew anxious to strike a more extreme blow for the cause.

On the night of October 16, 1859, he led a small band of less than 50 men in a raid against the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Their aim was to capture enough ammunition to lead a large operation against Virginia’s slaveholders. Brown’s men, including several blacks, captured and held the arsenal until federal and state governments sent troops and were able to overpower them.

John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry (also known as John Brown’s raid or The raid on Harper’s Ferry) was an effort by armed abolitionist John Brown to initiate an armed slave revolt in 1859 by taking over a United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown’s party of 22 was defeated by a company of U.S. Marines, led by First Lieutenant Israel Greene. Colonel Robert E. Lee was in overall command of the operation to retake the arsenal.

John Brown had originally asked Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, both of whom he had met in his transformative years as an abolitionist to join him in his raid, but Tubman was prevented by illness, and Douglass declined, as he believed Brown’s plan would fail .

The Kennedy Farmhouse served as “barracks, arsenal, supply depot, mess hall, debate club, and home.” It was very crowded and life there was tedious. Brown did not plan to have a sudden raid and escape to the mountains. Rather, he intended to use those rifles and pikes he captured at the arsenal, in addition to those he brought along, to arm rebellious slaves with the aim of striking terror in the slaveholders in Virginia.

They would free more slaves, obtain food, horses and hostages, and destroy slaveholders’ morale. Brown planned to follow the Appalachian Mountains south into Tennessee and even Alabama, the heart of the South, making forays into the plains on either side.

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, Brown left four of his men behind as a rear-guard: his son, Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, and Frank Meriam; he led the rest into the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown detached a party under John Cook Jr. to capture Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington, at his nearby Beall-Air estate, some of his slaves, and two relics of George Washington: a sword allegedly presented to Washington by Frederick the Great and two pistols given by the Marquis de Lafayette, which Brown considered talismans. The party carried out its mission and returned via the Allstadt House, where they took more hostages. Brown’s main party captured several watchmen and townspeople in Harpers Ferry.

Brown’s men needed to capture the weapons and escape before word could be sent to Washington. The raid was going well for Brown’s men. They cut the telegraph wire and seized a Baltimore & Ohio train passing through. A free black man was the first casualty of the raid. Hayward Shepherd, an African-American baggage handler on the train, confronted the raiders; they shot and killed him.

For some reason, Brown let the train continue, and the conductor alerted the authorities down the line. Brown had been sure that he would win the support of local slaves in joining the rebellion, but a massive uprising did not occur, because word had not been spread about the uprising, so the slaves nearby did not know about it. Although the white townspeople soon began to fight back against the raiders, Brown’s men succeeded in capturing the armory that evening.

Army workers discovered Brown’s men early on the morning of October 17. Local militia, farmers and shopkeepers surrounded the armory. When a company of militia captured the bridge across the Potomac River, any route of escape for the raiders was cut off. During the day, four townspeople were killed, including the mayor. Realizing his escape was cut, Brown took nine of his captives and moved into the smaller engine house, which would come to be known as John Brown’s Fort.

The raiders blocked entry of the windows and doors and traded sporadic gunfire with surrounding forces. At one point Brown sent out his son, Watson, and Aaron Dwight Stevens with a white flag, but Watson was mortally wounded and Stevens was shot and captured. The raid was rapidly failing. One of Brown’s men, William H. Leeman, panicked and made an attempt to flee by swimming across the Potomac River, but he was shot and fatally injured while doing so. During the intermittent shooting, Brown’s other son, Oliver, was also hit; he died after a brief period.

At around 3:00 p.m. a militia company led by Captain E.G. Alburtis arrived by train from Martinsburg, Virginia. Most of the militia members were Baltimore & Ohio Railroad employees. The militia forced the raiders inside the engine house. They broke into the guardroom and freed over two dozen prisoners. Eight militiamen were wounded. Alburtis said that he could have ended the raid with help from other citizens.

By 3:30 that afternoon, President James Buchanan ordered a company of U.S. Marines (the only government troops in the immediate area) to march on Harpers Ferry under the command of Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee, lieutenant colonel of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment. Lee had been on leave from his regiment, stationed in Texas, when he was hastily called to lead the detachment and had to command it while wearing his civilian clothes.

John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859; his trial riveted the nation, and he emerged as an eloquent voice against the injustice of slavery and a martyr to the abolitionist cause. Just as Brown’s courage turned thousands of previously indifferent northerners against slavery, his violent actions convinced slave owners in the South beyond doubt that abolitionists would go to any lengths to destroy the —peculiar institution.”

Rumors spread of other planned insurrections, and the South reverted to a semi–war status. Only the election of the anti–slavery Republican Abraham Lincoln as president in 1860 remained before the southern states would begin severing ties with the Union, sparking the bloodiest conflict in American history.