On June 25, 1941, President Roosevelt created the Committee on Fair Employment Practice, generally known as the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC), by signing Executive Order 8802, which stated, “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

A. Philip Randolph, founding president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, had lobbied with other activists for such provisions due to the wide discrimination against African Americans in employment across the country. With the buildup of defense industries before the United States entered the war, blacks were being excluded from economic opportunities. With all groups of Americans being asked to support the war effort, Randolph demanded changes in employment practice of the defense industries, which regularly excluded African Americans and other minorities based on race.

Together with other activists, Rudolph planned to muster tens of thousands of persons for a 1941 March on Washington to protest continued segregation in the military and discrimination in defense industries. A week before they planned march, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York met with him and other officials to discuss the President’s intent to issue an executive order announcing a policy of non-discrimination in Federal vocational and training programs.

Randolph and his allies convinced him that more was needed, especially directed at the booming defense industries.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 to prohibit discrimination among defense firms that had contracts with the government. He established the Fair Employment Practice Committee to implement this policy through education, accepting complaints of job discrimination, and working with industry on changing employment practices. The activists called off their march.

After the executive order was signed, Roosevelt appointed Mark Etheridge, a liberal editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal, to head the new agency. Etheridge brought “important political connections and public relations expertise to the job” but he “emphasized interracial cooperation over equality and refused to challenge the southern system of segregation.”

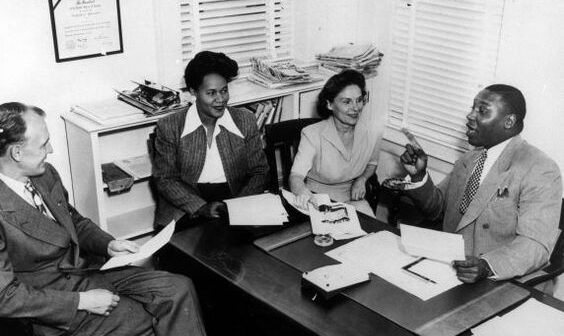

Knowing that industry was likely to be hostile, Randolph and other activists believed that the FEPC would depend on workers keeping their own records as to practices at work places and taking cases of discrimination to the committee.

The Fair Employment Practice Committee had a limited budget of $80,000 in its first year, paid from the emergency funds of the Office of the President (which continued to fund it, as it did some other agencies created by executive order). Etheridge needed to focus on a few activities in certain areas of the country. He held the first of the FEPC hearings in Los Angeles in October 1941.

Some companies admitted they were discriminating based on race when hiring for new job positions, but Etheridge did little to change their practices. This lack of enforcement caused many union leaders, civil rights leaders, government officials, and employers to doubt whether the FEPC and Executive Order could produce desired change.

The Fair Employment Practice Committee did not end racial discrimination in employment practices during World War II, but it did have a lasting effect in that era. It opened some doors, as far more of its cases were based on “refusal to hire” than “refusal to upgrade” or “discriminatory working conditions”. It apparently helped blacks enter “industries, firms, and occupations that otherwise might have remained closed to them.”

The operation of the FEPC supported the idea that “economic rights can be obtained principally by activity in the economic sphere: through education, protest, self-help, and, at times, intimidation.” It gained support of states and government to eliminate racial discrimination in employment practices. During its relatively short period of operations from 1941 to 1946, the FEPC encouraged the formation of other groups with similar goals, such as the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights supporting the National Council for a Permanent FEPC.

By opening some good-paying jobs in the defense industry, the FEPC created opportunity for African Americans. By 1950, compared to other men in comparable positions, those blacks who gained jobs in defense were making 14% more than their counterparts outside. The proportion of blacks in the defense industry did not decline after the war, suggesting that many men had gained an entree into important new work.

In 1948, President Truman asked Congress to approve a permanent FEPC, anti-lynching legislation, and the abolition of the poll tax in federal elections. A Democratic coalition prevented the legislation’s passage.

Still operating effectively with one-party systems in their states due to disenfranchisement of blacks at the turn of the century, Southern Democrats had powerful positions in Congress, controlling chairmanships of important committees, and opposed these measures.

In 1950, the House approved a permanent FEPC bill, but Southern senators filibustered and the bill failed. Congress has never enacted the FEPC into law. But New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Washington successfully enacted and enforced their own FEPC laws at the state level.