William Madison McDonald (June 22, 1866 – July 5, 1950), nicknamed “Gooseneck Bill”, was an African-American politician, businessman, and banker of great influence in Texas during the late nineteenth century. Part of the Black and Tan faction, by 1892 he was elected to the Republican Party of Texas’s state executive committee, as temporary chairman in 1896, and as permanent state chairman in 1898.

During this period, McDonald was also elected as top leader of two black fraternal organizations, serving as Grand Secretary of the state’s black Masons for 50 years. In 1906 he founded Fort Worth’s first African-American-owned bank as an enterprise of the state Masons; under his management, the bank survived the Great Depression. The black chapters of Masons banked with him, McDonald made loans to black businessmen, and he became probably the first black millionaire in Texas.

Named after William Shakespeare and James Madison, William Madison McDonald was born in 1866 in College Mound, Texas, little more than a year after the end of the American Civil War. His father George McDonald was a former slave from Tennessee. He was once held by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, according to a 2008 report by the Dallas Morning News.

His mother was Flora (née Scott) McDonald of Alabama, described by one source as a “free woman of color” before the war, and by another as a “former slave.” George McDonald was a farmer and blacksmith. After Flora died when William was a child, his father married Belle Crouch.

As a teenager, McDonald went to work for rancher and lawyer Captain Z. T. Adams, who took an interest in him. He began teaching the youth about business and law. After graduating from high school in 1884, with the help of Adams and others, McDonald attended Roger Williams University in Nashville, Tennessee. It had been established by the Baptist Church of the North in 1866 as a historically black college, and was important for educating generations of African-American leaders in the South.

After returning to Texas, McDonald served as principal of an African-American high school in Forney, Texas, for several years, in a rural area outside Dallas. The Reconstruction-era legislature had established the state’s first public school system. In order to gain approval, legislators agreed to let local boards determine whether schools would be racially segregated. Education was a high priority for freedmen and their children.

McDonald married Alice Gibson, who was a teacher at his school. McDonald helped organized a black state fair in North Texas.

McDonald became active in the Republican Party and encouraged blacks to vote; he helped organize the party in Kaufman County and the region.

In 1892, McDonald was elected to the Republican Party of Texas’s state executive committee. He was a power in state politics for more than thirty years, and became a leader of the “Black and Tan” faction, African Americans within the Republican Party. He teamed up politically with white businessman Ned Green of Fort Worth, the son of the wealthiest woman in America. Green supported the “Black and Tan” faction in Republican internal struggles.

At the 1896 Republican National Convention, McDonald was given the nickname “Gooseneck Bill” by a Dallas Morning News reporter. In 1898 he was defeated for state chairman of the Republican Party by Henry Clay Ferguson; the continuing rivalry of their factions resulted in a decrease in black influence in the party.

Through these years, McDonald had also been active in black fraternal organizations, which developed rapidly throughout Texas and the South after the war as blacks established independent networks. He was elected as the Supreme Grand Chief of the Seven Stars of Consolidation of America.

In 1890, he also joined the Prince Hall Freemasonry. In 1899 he was elected as Right Worshipful Grand Secretary of the African-American Texas Masons, a position that provided operating direction to the group. Under his leadership, the Masons developed several business enterprises: started “a cotton mill, published a magazine, offered insurance to members, and established a bank in Fort Worth.” He remained the Grand Secretary of the Texas Masons for 50 years.

White Democrats regained power in the state legislature and passed laws making voter registration more difficult, requiring payment of poll taxes and, later, restricting minority participation by the use of white primaries. These actions resulted in effective disenfranchisement of blacks, Mexican Americans, and many poor whites in the state. More than 100,000 blacks voted statewide in elections of the 1890s, but by 1906, their number had dropped to 5,000.

“Lily White” Republicans essentially drove the “Black and Tan” faction out of power in the party in 1900. McDonald and the Black and Tans temporarily regained power in 1912, before losing it again. McDonald continued to be a notable figure in the national Republican Party, however, attending many national conventions.

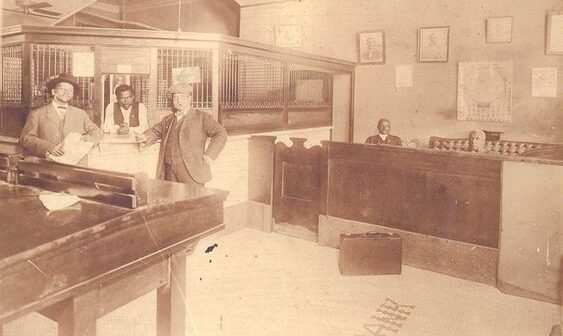

McDonald turned his energies to business, though he retained an interest in politics. He moved to Fort Worth in 1906, where he became manager of the Fraternal Bank and Trust Company, founded by the Masons as the city’s first African-American-owned bank. For a time, it was the bank used by most of the black Mason chapters in the state. With their deposits, McDonald had capital for providing loans to African-American entrepreneurs and could encourage development of their businesses.

In that segregated era, blacks had great difficulty gaining financing from white-owned banks. Under McDonald’s management, the bank survived the Great Depression, when many other banks went under. According to a 2008 report by the Dallas Morning News, McDonald was “probably Texas’ first black millionaire.”

Disappointed with Texas Republicans, McDonald increasingly exercised independence in supporting Presidential candidates: favoring Progressive Robert M. La Follette, Sr. and Democrats Al Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt. He returned to the Republican Party to support Thomas E. Dewey in his presidential bid against Harry Truman.

McDonald died on July 5, 1950, in Fort Worth, where he was buried in Trinity Cemetery. He was survived by his fifth wife. His only child, a son, had predeceased him by thirty years.

In 2002, Forney, Texas, erected a historical marker to acknowledge native son McDonald and his achievements; its text includes the following: “Throughout his life, McDonald was a leader in the struggle for social justice, advocating persistence and civic and moral responsibility as the steps to equality.”