-The 1811 German Coast Uprising was a revolt of black slaves in parts of the Territory of Orleans on January 8–10, 1811. The uprising occurred on the east bank of the Mississippi River in what are now St. John the Baptist and St. Charles Parishes, Louisiana. While the slave insurgency was the largest in US history, the rebels killed only two white men. Confrontations with militia and executions after trial killed 95 black people. There is barely any reference to this slave uprising.

-Between 64 and 125 enslaved men marched from sugar plantations near present-day LaPlace on the German Coast toward the city of New Orleans. They collected more men along the way. Some accounts claimed a total of 200 to 500 slaves participated. During their two-day, twenty-mile march, the men burned five plantation houses, several sugarhouses, and crops. They were armed mostly with hand tools, knives, and clubs.

-White men led by officials of the territory formed militia companies to hunt down and kill the insurgents. Over the next two weeks, white planters and officials interrogated, tried and executed an additional 44 insurgents who had been captured. Executions were generally by hanging or firing squad, with some dismembering of the remains. Heads were displayed on pikes to intimidate other slaves.

-Since 1995, the African American History Alliance of Louisiana has led an annual commemoration in January of the uprising, in which they have been joined by some descendants of participants in the revolt. The German Coast was an area of sugar plantations, with a dense slave population. According to some accounts, blacks outnumbered whites by nearly five to one. More than half of those enslaved may have been born outside Louisiana, many in Africa.

-In the overall Territory of Orleans, from 1803 to 1811, the free black population nearly tripled, to 5,000, with 3,000 Haiti migrants from Cuba in 1809–1810. In Saint-Domingue they had enjoyed certain rights as gens de couleur.

-After the US negotiated the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Territorial Governor William C.C. Claiborne struggled with the diverse population. Not only were there numerous French and Spanish-speaking people, but there was a much greater proportion of native Africans among the slaves than in more northern U.S. states. In addition, the mixed-race Creole and French-speaking population grew markedly with refugees from Haiti following the successful slave revolution. The American Claiborne was not used to a society with the number of free people of color that Louisiana had—but he worked to continue their role in the militia that had been established under Spanish rule. He had to deal with the competition for power between long-term French Creole residents and new US settlers in the territory. Lastly, Claiborne was suspicious that the Spanish might encourage an insurrection. He struggled to establish and maintain his authority.

-The waterways and bayous around New Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain made transportation and trade possible, but also provided easy escapes and nearly impenetrable hiding places for runaway slaves. Some maroon colonies continued for years within several miles of New Orleans. With the spread of ideas of freedom from the French and Haitian revolutions, European-Americans worried about slave uprisings in the Louisiana area.

-A group of Africans who had been forcefully enslaved met on January 6, 1811. It was a period when work had relaxed on the plantations after the fierce weeks of the sugar harvest and processing. As planter James Brown testified weeks later, “The black Quamana [Kwamena, meaning “born on Saturday”], owned by Mr. Brown, and the mulatto Harry, owned by Messrs. Kenner & Henderson, were at the home of Manuel Andry on the night of Saturday–Sunday of the current month in order to deliberate with the mulatto Charles Deslondes, chief of the brigands.” Slaves had spread word of the planned uprising among the slaves at plantations up and down the “German Coast”, along the Mississippi River.

-The revolt began on January 8 at the Andry plantation. After striking and badly wounding Manuel Andry, the slaves killed his son Gilbert. “An attempt was made to assassinate me by the stroke of an axe,” Andry wrote. “My poor son has been ferociously murdered by a horde of brigands who from my plantation to that of Mr. Fortier have committed every kind of mischief and excesses, which can be expected from a gang of atrocious bandittis of that nature.”

-The rebellion gained momentum quickly. The 15 or so slaves at Andry’s plantation, about 30 miles (50 km) upriver from New Orleans, joined another eight slaves from the next-door plantation of the widows of Jacques and Georges Deslondes. This was the home plantation of Charles Deslondes, a field laborer later described by one of the captured slaves as the “principal chief of the brigands.” Small groups of slaves joined from every plantation the rebels passed. Witnesses remarked on their organized march. Although they carried mostly pikes, hoes, axes, and few firearms, they marched to drums while some carried flags. From 10–25% of any given plantation’s slave population joined with them.

-At the plantation of James Brown, Kook, one of the most active participants and key figures in the story of the uprising, joined the insurrection. At the next plantation down, Kook attacked and killed François Trépagnier with an axe. He was the second and last planter killed in the rebellion. After the band of slaves passed the LaBranche plantation, they stopped at the home of the local doctor. Finding the doctor gone, Kook set his house on fire.

-Some planters testified at the trials in parish courts that they were warned by their slaves of the uprising. Others regularly stayed in New Orleans, where many had town houses, and trusted their plantations to overseers to run. Planters quickly crossed the Mississippi River to escape the insurrection and to raise a militia.

-As the slave party moved downriver, they passed larger plantations, from which many slaves joined them. Numerous slaves joined the insurrection from the Meuillion plantation, the largest and wealthiest plantation on the German Coast. The rebels laid waste to Meuillion’s house. They tried to set it on fire, but a slave named Bazile fought the fire and saved the house.

-After nightfall the slaves reached Cannes-Brulées, about 15 miles (24 km) northwest of New Orleans. The men had traveled between 14 and 22 miles (23 and 35 km), a march that probably took them seven to ten hours. By some accounts, they numbered “some 200 slaves,” although other accounts estimated up to 500. As typical of revolts of most classes, free or slave, the insurgent slaves were mostly young men between the ages of 20 and 30. They represented primarily lower-skilled occupations on the sugar plantations, where slaves labored in difficult conditions.

-After being injured, Col. Andry went to the other side of the river to round up a militia organized by planters, who began pursuing the slave rebels. By noon on January 9, the residents of New Orleans had heard of the insurrection on the German Coast. Over the next six hours, General Wade Hampton I, Commodore John Shaw, and Governor William C.C. Claiborne sent two companies of volunteer militia, 30 regular troops, and a detachment of 40 seamen to fight the slaves.

-By about 4 a.m., the troops reached the plantation of Jacques Fortier, where Hampton thought the insurgents had encamped for the night. The insurgents had left hours before Hampton’s arrival and started back upriver. Over the next few hours, they traveled about 15 miles (24 km) back up the coast and neared the plantation of Bernard Bernoudy.

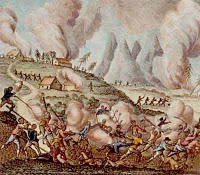

-There, planter Charles Perret, under the command of the badly injured Andry and in cooperation with Judge St. Martin, had assembled a militia of about 80 men from the opposite side of the river. At about 9 o’clock, this second militia discovered the slaves moving toward high ground on the Bernoudy estate. Perret ordered the militia to attack the slaves. Perret later wrote that there were about 200 slaves, about half on horseback. (Most accounts said only the leaders were mounted, and historians believe it unlikely the slaves could have gathered so many mounts.)

-The battle was brief. Within a half-hour of the attack, 40 to 45 slaves had been killed and the remainder slipped away into the woods. Perret and Andry’s militia tried to pursue slaves into the woods and swamps, but it was difficult territory.

-On January 11, the militia captured Charles Deslondes, whom Andry considered “the principal leader of the bandits.” The militia did not hold him for trial or interrogation. Samuel Hambleton described Deslonde’s fate: “Charles [Deslondes] had his hands chopped off then shot in one thigh & then the other, until they were both broken – then shot in the Body and before he had expired was put into a bundle of straw and roasted!”